![Vivaldi - Complete Cello Concertos - Ofra Harnoy - [RCA Red Seal, 1995, 4CD's]](http://i178.photobucket.com/albums/w246/bagabum/Folder.jpg) |

|

Label: RCA No: 67886 (RCA Viktor Red Seal)

Genre: Classical

Style: Cello Concertos

Format: ape+cue+logs, covers

Ofra Harnoy - Cello

Paul Robinson - Conductor, Liner Notes

Richard Stamp - Conductor

Igor Oistrakh - Violin

Elizabeth Keenan - Harpsichord

Valerie Weeks - Harpsichord, Organ

James McKay - Bassoon

Mihai Tetel - Continuo

Robert Dodson - Continuo

Toronto Chamber Orchestra - Orchestra

Jacob Harnoy - Musical Supervision, Producer, Engineer

Larry Lake - Engineer

David Burnham - Engineer

Jeff Stubbins - Production Assistant

Clive Allen - Production Assistant

Janet Berridge - Liner Note Translation

Michael Berridge - Liner Note Translation

Olaf Joksch - Liner Notes

Joseph J. Stelmach - Artwork

Carol Weinberg - Photography

Of all the great composers, we know perhaps the least about Antonio Vivaldi. There are hundreds of Vivaldi concertos, for a wide variety of different instruments, which are popular today, most notably the set of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons. However, there are literally hundreds of other pieces that remain both unknown and unperformed. The sheer volume of this output is viewed by some as a negative thing. How could a composer who writes so much, they say, produce anything of quality?

This disparaging view is invariably based on ignorance. Such people have never examined the music. The fact of the matter is that for all of Vivaldi’s huge volume of music for violin, flute, oboe, bassoon, cello and many other instruments, singly or in combination, both the high standard and the variety are amazing. Nor can we stop there. He also composed dozens of sacred and secular large-scale vocal works and, by his own account, 94 operas. The music for many of them has been lost, but enough survives to suggest that a major revival of his operas is long overdue.

If much of Vivaldi’s music is still unknown, the facts of his life are almost totally obscure. We know that he trained to be a priest but forsook this calling to make his way as a musician. For most of his creative life, he was in charge of music at the Ospedale delta Pieta, an orphanage for girls in Venice. Later in his career, he was preoccupied with opera. He continued to live in Venice but traveled to other cities in Italy and to Germany, Amsterdam and Vienna, where he died.

We know of 27 cello concertos by Vivaldi. It is not a large number when compared with his nearly 400 violin concertos, 40 bassoon concertos, etc... The large creative output is not unusual for the period and is comparable to that of Bach, Handel, Haydn and Mozart. Yet, for Vivaldi, no information is available about the circumstances, motivation, first performance or inspiration behind its creation. Some concertos make greater technical demands on the soloist than others; this may suggest that he wrote them for different players: some for accomplished soloists and others for his students at the Ospedale.

In Vivaldi’s period a keyboard instrument such as harpsichord or the organ was used (with a cello) as a continuo instrument with the orchestra. However, neither Vivaldi nor his contemporaries ever specified which particular keyboard instrument they had in mind. For these recordings, we have chosen the harpsichord in the quick outer movements and the organ for the slow middle movements, where its long, sustained notes blend so well.

Close examination of the concertos makes one increasingly aware of the differences between them and what makes each one unique.

The driving, machinelike energy of the Concerto in D Minor, RV 406, is unforgettable. Notice also, how the rests between the opening phrases resonate! The slow movement is memorable for its expressive eloquence, its unison phrases seeming to foreshadow the beginning of the slow movement of Beethoven’s G major piano concerto. The Finale is a rare example where the last movement is in minuet form; throughout this movement, the solo cello part becomes increasingly difficult.

The A Minor Concerto, RV 422, is interesting for the clever way in which the opening phrase is divided between the first and second violins. As often in these concertos, in the slow movement the soloist is accompanied only by the continuo players, but here the continuo cello creates a lovely dialogue with the soloist. The lively third movement, in 9/8 time, suggests the Italian dance form, the tarantella.

The G Major Concerto, RV 414, is particularly notable for its slow movement. The opening and closing tutti, with their magically inspired base lines, as well as the expressive solo cello line sung in a poetic combination of mystery and lamentation are as sublimely beautiful as anything Vivaldi ever wrote.

The tempo marking for the first movement of RV 424 is Allegro non molto. Vivaldi’s markings for the quick movements are usually short: Allegro (fast and lively). Such tempo indication are all that a performer can go by. (The invention of the metronome was still a century away.) "Non molto" (not too much) provides somewhat added indication to the performers when approaching this uniquely inspired movement, with its dark, meditative key of B minor; an effect of special beauty occurs toward the end, when the soloist is accompanied only by violins and violas for a stretch of 17 bars. The Largo’s accompaniment base line consists largely of repeated notes and a simple harmony; the result is far from dull, however, because of Vivaldi’s genius for creating almost endlessly varied embellishment in the melodic line.

Although the orchestration of these concertos is always the same (strings and keyboard continuo), the opening of the D Major Concerto, RV 403, has such dotted fanfares that we seem to hear additional instruments-trumpets and drums.

In the slow movement of the F Major Concerto, RV 412, Vivaldi’s embellished melodic line is such that we are not listening to the usual melody and accompaniment but to a melody with simultaneous embellishments in different parts. The orchestra provides a beautiful halo effect for the soloist.

Notice how, in the opening movement of the C Minor Concerto, RV 402, the second violins reply canonically a half bar later each time the main theme is presented. This concerto is one of those works with a solo part of modest technical difficulty when compared with the others in this album. It is, perhaps, one of those written for the students at the Ospedale. Even if it may have been intended as a teaching piece, the result is nonetheless a work of quality. After all, many other great composers, from Bach to Bartok, have written wonderful music to guide their students through the stages of their development.

Paul Robinson

Ofra Harnoy, in a remarkably short time, has established herself as one of this generation’s leading cellists. Described by The New York Times as "born to the instrument," she is also one of Canada’s most celebrated personalities and was recently selected by MacLean’s magazine (Canada’s national weekly) as one of 12 distinguished Canadians, in all fields, who bring the most credit to Canada internationally.

Miss Harnoy was born in Israel in 1965 and studied with her father, with William Pleeth in London, Vladimir Orloff in Toronto, and in master classes with Mstislav Rostropovich, Pierre Fournier and Jacqueline du Pre. Soon after her family moved to Canada, she made her professional debut, at age 10, as soloist with orchestra. Since then she has appeared with numerous major orchestras and in recitals in the United States, Canada, England, France, Germany, Holland, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, Israel, Japan and Australia, and she has been featured on nationally televised solo concerts and documentaries in Canada, Japan, Australia and throughout Europe.

After winning major Canadian competitions, Miss Harnoy won the 1982 Concert Artists Guild award in New York; this resulted in her solo-orchestral and recital debuts in Carnegie Hall, which won both public and critical raves. Soon after, she was selected Young Musician of the Year for 1983 by Musical America magazine. In 1987/88 and again in 1988/89 she won the JUNO award (Canada) as Best Classical Soloist, and in 1988, she received the Grand Prix du Disque. Several of her highly acclaimed recordings have been noted as "Best of the Year" or "Critics Choice" by magazines such as Gramophone, High Fidelity and Ovation. Miss Harnoy gave the world premiere performance (and recording) of the Offenbach Cello Concerto (1983) and the North American premiere of the Bliss Cello Concerto (1984), and in 1987 and ‘89 made world-premiere recordings of several Vivaldi concertos.

Paul Robinson is Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Toronto Philharmonic Orchestra and the Toronto Chamber Orchestra. In addition, he has been Music Director of one of North America’s foremost classical music radio stations (CJRT-FM in Toronto) and its orchestra since 1971. He appears frequently as guest conductor across Canada, the United States, Europe and the Far East. He is the author of four books on conductors and of numerous articles on musical subjects.

Paul Robinsone

Genre: Classical

Style: Cello Concertos

Format: ape+cue+logs, covers

Ofra Harnoy - Cello

Paul Robinson - Conductor, Liner Notes

Richard Stamp - Conductor

Igor Oistrakh - Violin

Elizabeth Keenan - Harpsichord

Valerie Weeks - Harpsichord, Organ

James McKay - Bassoon

Mihai Tetel - Continuo

Robert Dodson - Continuo

Toronto Chamber Orchestra - Orchestra

Jacob Harnoy - Musical Supervision, Producer, Engineer

Larry Lake - Engineer

David Burnham - Engineer

Jeff Stubbins - Production Assistant

Clive Allen - Production Assistant

Janet Berridge - Liner Note Translation

Michael Berridge - Liner Note Translation

Olaf Joksch - Liner Notes

Joseph J. Stelmach - Artwork

Carol Weinberg - Photography

Of all the great composers, we know perhaps the least about Antonio Vivaldi. There are hundreds of Vivaldi concertos, for a wide variety of different instruments, which are popular today, most notably the set of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons. However, there are literally hundreds of other pieces that remain both unknown and unperformed. The sheer volume of this output is viewed by some as a negative thing. How could a composer who writes so much, they say, produce anything of quality?

This disparaging view is invariably based on ignorance. Such people have never examined the music. The fact of the matter is that for all of Vivaldi’s huge volume of music for violin, flute, oboe, bassoon, cello and many other instruments, singly or in combination, both the high standard and the variety are amazing. Nor can we stop there. He also composed dozens of sacred and secular large-scale vocal works and, by his own account, 94 operas. The music for many of them has been lost, but enough survives to suggest that a major revival of his operas is long overdue.

If much of Vivaldi’s music is still unknown, the facts of his life are almost totally obscure. We know that he trained to be a priest but forsook this calling to make his way as a musician. For most of his creative life, he was in charge of music at the Ospedale delta Pieta, an orphanage for girls in Venice. Later in his career, he was preoccupied with opera. He continued to live in Venice but traveled to other cities in Italy and to Germany, Amsterdam and Vienna, where he died.

We know of 27 cello concertos by Vivaldi. It is not a large number when compared with his nearly 400 violin concertos, 40 bassoon concertos, etc... The large creative output is not unusual for the period and is comparable to that of Bach, Handel, Haydn and Mozart. Yet, for Vivaldi, no information is available about the circumstances, motivation, first performance or inspiration behind its creation. Some concertos make greater technical demands on the soloist than others; this may suggest that he wrote them for different players: some for accomplished soloists and others for his students at the Ospedale.

In Vivaldi’s period a keyboard instrument such as harpsichord or the organ was used (with a cello) as a continuo instrument with the orchestra. However, neither Vivaldi nor his contemporaries ever specified which particular keyboard instrument they had in mind. For these recordings, we have chosen the harpsichord in the quick outer movements and the organ for the slow middle movements, where its long, sustained notes blend so well.

Close examination of the concertos makes one increasingly aware of the differences between them and what makes each one unique.

The driving, machinelike energy of the Concerto in D Minor, RV 406, is unforgettable. Notice also, how the rests between the opening phrases resonate! The slow movement is memorable for its expressive eloquence, its unison phrases seeming to foreshadow the beginning of the slow movement of Beethoven’s G major piano concerto. The Finale is a rare example where the last movement is in minuet form; throughout this movement, the solo cello part becomes increasingly difficult.

The A Minor Concerto, RV 422, is interesting for the clever way in which the opening phrase is divided between the first and second violins. As often in these concertos, in the slow movement the soloist is accompanied only by the continuo players, but here the continuo cello creates a lovely dialogue with the soloist. The lively third movement, in 9/8 time, suggests the Italian dance form, the tarantella.

The G Major Concerto, RV 414, is particularly notable for its slow movement. The opening and closing tutti, with their magically inspired base lines, as well as the expressive solo cello line sung in a poetic combination of mystery and lamentation are as sublimely beautiful as anything Vivaldi ever wrote.

The tempo marking for the first movement of RV 424 is Allegro non molto. Vivaldi’s markings for the quick movements are usually short: Allegro (fast and lively). Such tempo indication are all that a performer can go by. (The invention of the metronome was still a century away.) "Non molto" (not too much) provides somewhat added indication to the performers when approaching this uniquely inspired movement, with its dark, meditative key of B minor; an effect of special beauty occurs toward the end, when the soloist is accompanied only by violins and violas for a stretch of 17 bars. The Largo’s accompaniment base line consists largely of repeated notes and a simple harmony; the result is far from dull, however, because of Vivaldi’s genius for creating almost endlessly varied embellishment in the melodic line.

Although the orchestration of these concertos is always the same (strings and keyboard continuo), the opening of the D Major Concerto, RV 403, has such dotted fanfares that we seem to hear additional instruments-trumpets and drums.

In the slow movement of the F Major Concerto, RV 412, Vivaldi’s embellished melodic line is such that we are not listening to the usual melody and accompaniment but to a melody with simultaneous embellishments in different parts. The orchestra provides a beautiful halo effect for the soloist.

Notice how, in the opening movement of the C Minor Concerto, RV 402, the second violins reply canonically a half bar later each time the main theme is presented. This concerto is one of those works with a solo part of modest technical difficulty when compared with the others in this album. It is, perhaps, one of those written for the students at the Ospedale. Even if it may have been intended as a teaching piece, the result is nonetheless a work of quality. After all, many other great composers, from Bach to Bartok, have written wonderful music to guide their students through the stages of their development.

Paul Robinson

Ofra Harnoy, in a remarkably short time, has established herself as one of this generation’s leading cellists. Described by The New York Times as "born to the instrument," she is also one of Canada’s most celebrated personalities and was recently selected by MacLean’s magazine (Canada’s national weekly) as one of 12 distinguished Canadians, in all fields, who bring the most credit to Canada internationally.

Miss Harnoy was born in Israel in 1965 and studied with her father, with William Pleeth in London, Vladimir Orloff in Toronto, and in master classes with Mstislav Rostropovich, Pierre Fournier and Jacqueline du Pre. Soon after her family moved to Canada, she made her professional debut, at age 10, as soloist with orchestra. Since then she has appeared with numerous major orchestras and in recitals in the United States, Canada, England, France, Germany, Holland, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, Israel, Japan and Australia, and she has been featured on nationally televised solo concerts and documentaries in Canada, Japan, Australia and throughout Europe.

After winning major Canadian competitions, Miss Harnoy won the 1982 Concert Artists Guild award in New York; this resulted in her solo-orchestral and recital debuts in Carnegie Hall, which won both public and critical raves. Soon after, she was selected Young Musician of the Year for 1983 by Musical America magazine. In 1987/88 and again in 1988/89 she won the JUNO award (Canada) as Best Classical Soloist, and in 1988, she received the Grand Prix du Disque. Several of her highly acclaimed recordings have been noted as "Best of the Year" or "Critics Choice" by magazines such as Gramophone, High Fidelity and Ovation. Miss Harnoy gave the world premiere performance (and recording) of the Offenbach Cello Concerto (1983) and the North American premiere of the Bliss Cello Concerto (1984), and in 1987 and ‘89 made world-premiere recordings of several Vivaldi concertos.

Paul Robinson is Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Toronto Philharmonic Orchestra and the Toronto Chamber Orchestra. In addition, he has been Music Director of one of North America’s foremost classical music radio stations (CJRT-FM in Toronto) and its orchestra since 1971. He appears frequently as guest conductor across Canada, the United States, Europe and the Far East. He is the author of four books on conductors and of numerous articles on musical subjects.

Paul Robinsone

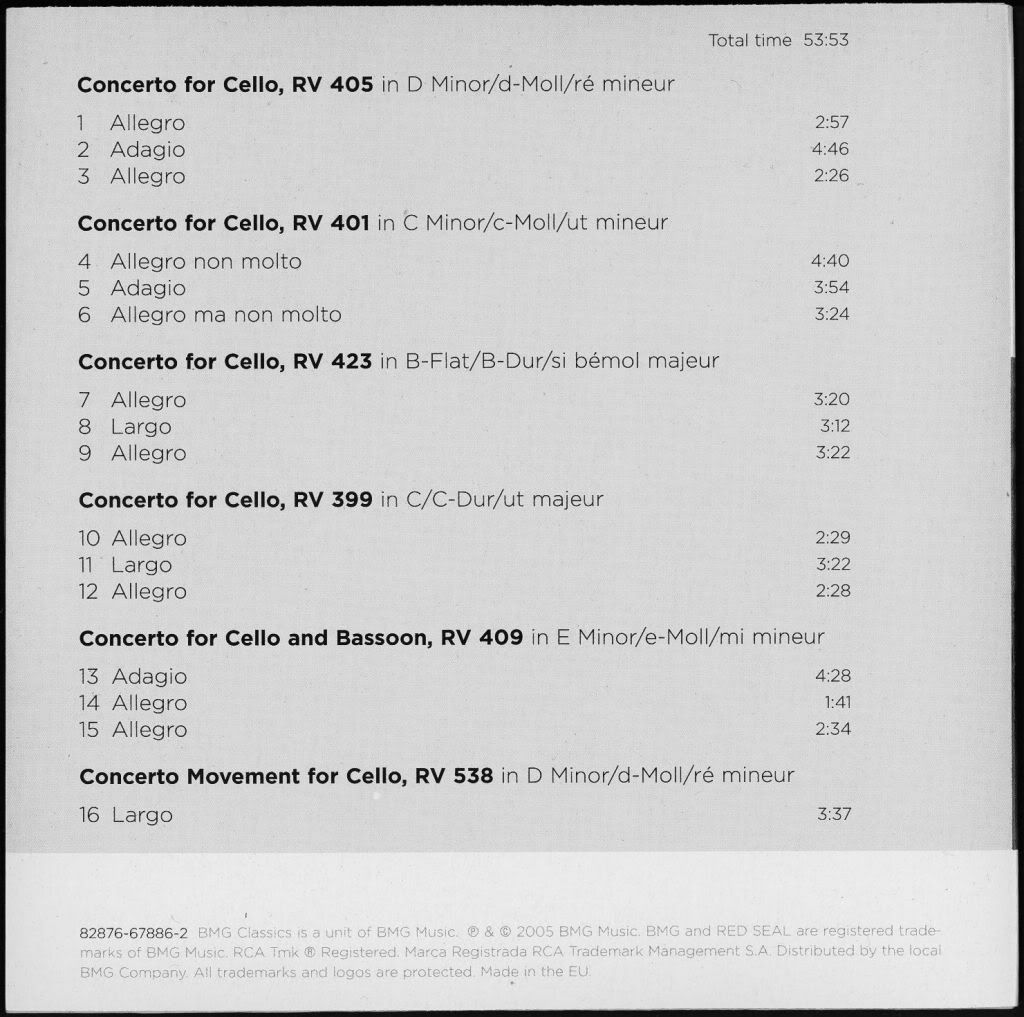

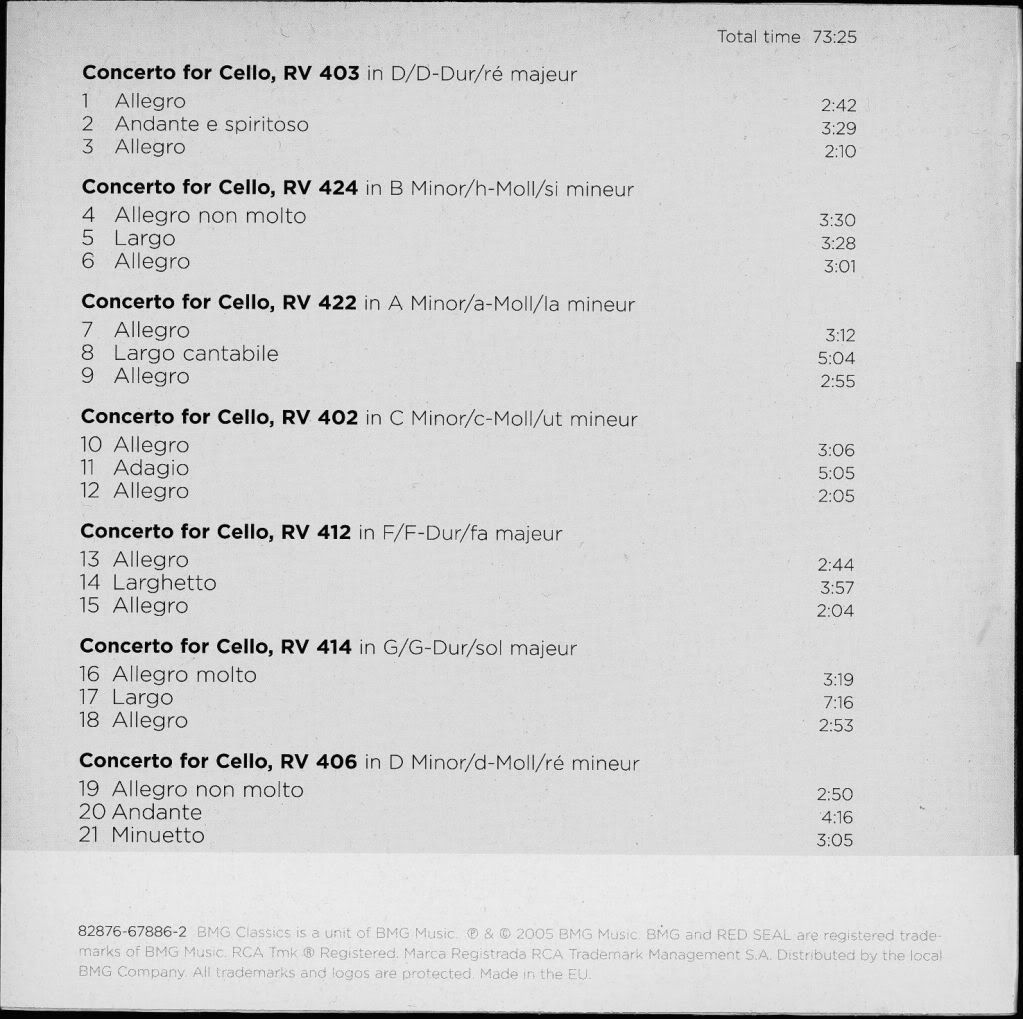

| SPOILER (Covers and Backs) |

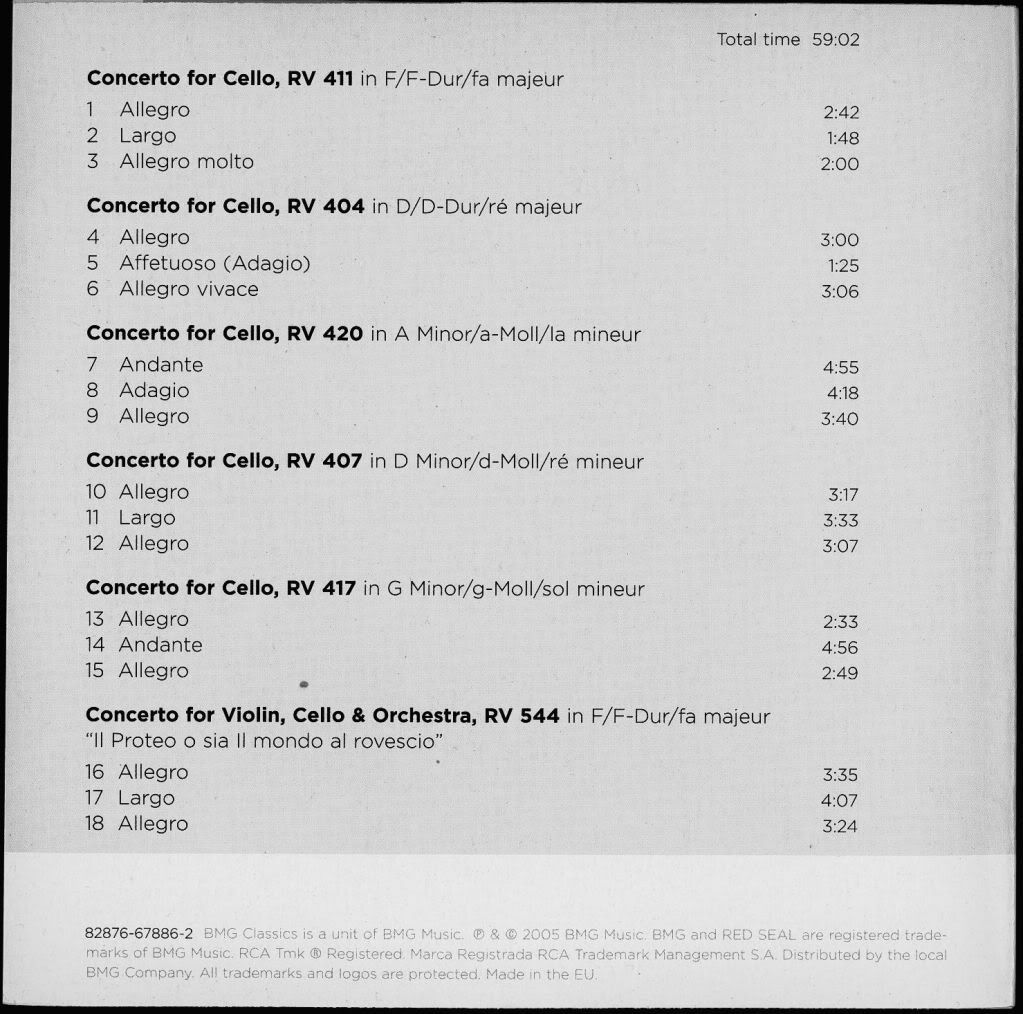

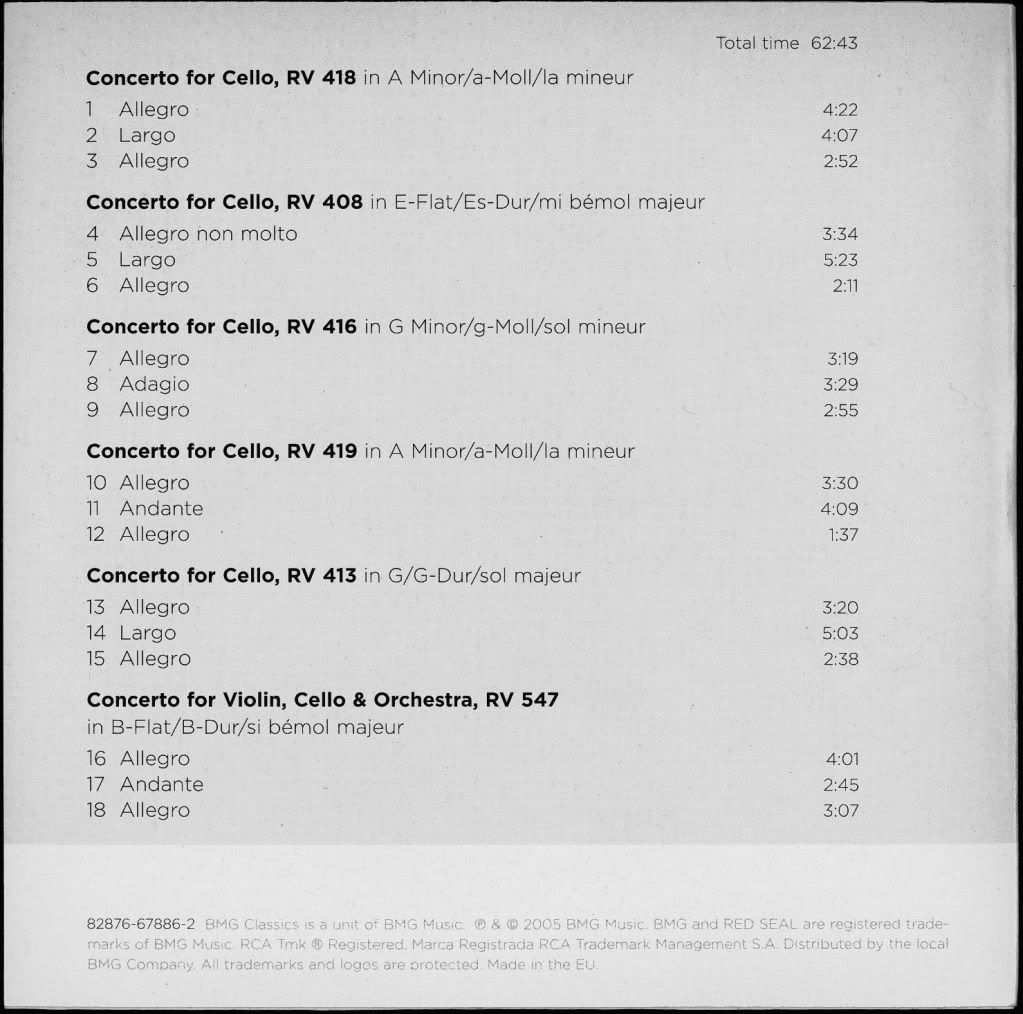

| SPOILER (Tracklists:) |

| SPOILER (log files) |