|

| NetLab · Rules · Torrent Tracker · Have a problem? · Eng/Rus |

Help Help

Search Search

Members Members

Gallery Gallery

Calendar Calendar

|

| Welcome Guest ( Log In | Register | Validation ) | Resend Validation Email |

|

Posted: 02-09-2011, 21:33

(post 1, #1028696)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Pro Member Group: Members Posts: 695 Warn:0% |

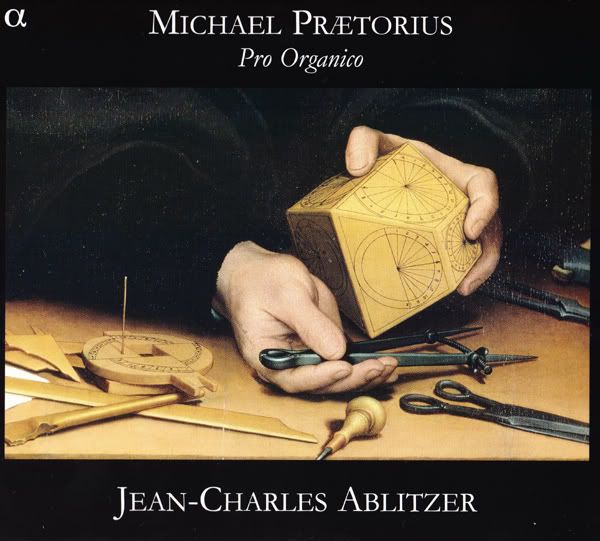

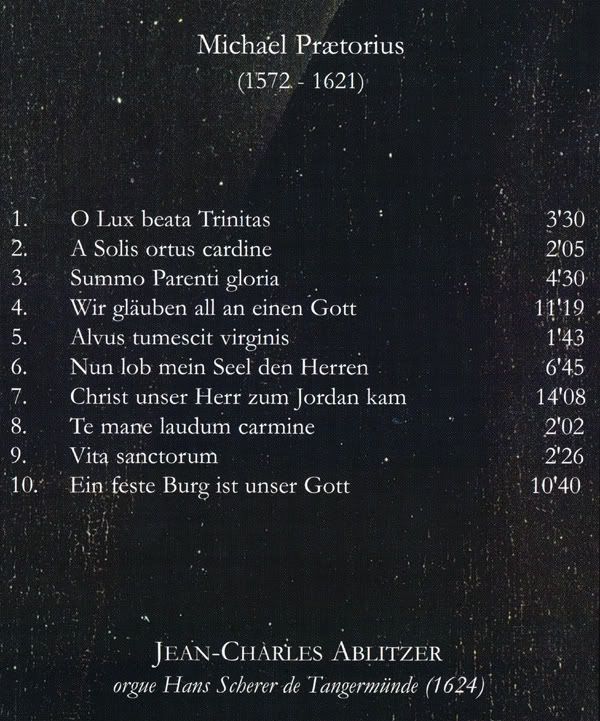

Michael Praetorius (1571 - 1621) Pro Organico Label: Alpha Productions, Alpha 114 Year: 2007 Performer: Jean-Charles Ablitzer - organ Tracklist: 01. Hymnus in festo trinitatis: O Lux beata Trinitas 3:28 02. Hymnus in festo nativitatis Christi: A Solis ortus cardine 2:04 03. Hymnus in festo nativitatis Christi: Summo Parenti gloria 4:30 04. Choralfantasia: Wir glauben all an einen Gott 11:20 05. Hymnus in adventu domini: Alvus tumescit virginis 1:41 06. Nun lob mein Seel den Herren: Prima variatio - Secunda variatio 6:43 07. Choralfantasia: Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam 14:05 08. Hymnus in festo trinitatis: Te mane laudum carmine 2:02 09. Hymnus in festo resurrectionis: Vita sanctorum 2:21 10. Choralfantasia: Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott 10:40 The works of Michael Praetorius (1571-1621), an outstanding composer and great innovator, have mainly come to the contemporary public’s attention thanks to his collection of dances under the name of Terpsichore and to his theoretical writings. Jean-Charles Ablitzer here gives us the first recording of 10 organ pieces selected from his Musae Soniae (phantasies on Lutherian melodies) and from his Hymnodia Sonia (Latin hymns). This interpretation, already acclaimed by a " Choc " from the Monde de la Musique, reveals Praetorius as an inspired and gentle colourist, whose musical idiom will leave a deep imprint on the first generation of baroque composers. The musicological rigour and the great sensitivity of the interpreter is further expressed by the choice of the historic organ of the church of St. Stephan in Tangermunde. Not only is it contemporary of the composer, but an identical model by the same maker is extensively described in Preatorius’ Syntagma Musicum. For once, as a unique exception, Alpha forfeits its role as a producer in order to bring this record to the public. It had been auto-produced by the artist but never commercialised while its unique quality soon turned it into an absolute, although unavailable reference. Michael Praetorius, as seen through his music, is a genius with a truly universal mind, a composer constantly searching for new forms of musical expression. It is hard to explain why his music has not received its just recognition. Strangely, only his collection of dance music Terpsichore is widely known, and these pieces scarcely show him at his true best. He is also known for his treatise Syntagma Musicum (three volumes: 1615, 1618 and 1619), one of the most important theoretical and didactic works of the century. The list of his musical works is impressive: Musae Sioniae (nine volumes published between 1605 and 1610, containing over 1200 pieces of music for voices and instruments), Musarum Sioniarum Moteae et Psalmi Latini (publ.1607), Megalinodia Sionia, Missodia Sionia and Hymnodia Sionia (1611), Terpsichore (1612), Urania (1613), Polyhymnia Caduceatrix et Panegyrica (1619), Polyhymnia Exercicatrix (1619). The struggle to complete this Herculean task led to his untimely death. Michael Praetorius was born in 1572 at Creuzburg an der Werra, a charming village which nestles beneath a castle only a few kilometres from Eisenach. His father and two elder brothers being pastors, it is scarcely surprising that he received a strict Lutheran upbringing, before going at the age of fourteen to the University of Frankfurt an der Oder to study theology and philosophy, being employed there as organist around 1587. It is not known why he left Frankfurt in 1589, before completing his studies, or what became of him for the next five years. In 1594 he was engaged by Duke Heinrich Julius of Braunschweig-Liineburg, Bishop of Halberstadt. First, he was appointed chapel organist at Groningen Castle, one of the Duke's favourite seats. In 1603 Praetorius married Anna Lakemacher of Halberstadt, and they had two sons, Michael (b.1604) and Ernst (b.1606). In 1604 he was appointed Kappelmeister at the court of Wolfenbuttel, the chief residence of Duke Heinrich Julius. Meanwhile, at Groningen the Duke had had a 59-stop organ built in 1596 by David Becken of Halberstadt, and 53 organist from all over Germany were invited to the inaugural festivities. This instrument, with its rich and varied tone colours, is described in Syntagma Musicum. It comprised six divisions over two manuals and Pedal. While virtually nothing remains of the castle today, the cases of the organ can be found in two nearby churches, having been re-used for other instruments. The main body of the case and the Pedal towers are in the Martinikirche at Halberstadt, while the Ruckpositiv is in the village of Harsleben. While still employed at Wolfenbuttel, Praetorius was appointed Director of Music to the House of Saxony at Dresden, and in the course of his duties travelled widely in Central Europe, meeting and working with Heinrich Schutz, Samuel Scheldt and other prominent musicians. On the death of Duke Heinrich Julius in 1613, Praetorius devoted himself exclusively to the crushing task of editing his works until his own death at Wolfenbuttel in 1621. He was buried close to his home, at the foot of the organ in the neighbouring Hauptkirche Beatae Mariae Virginis. Praetorius's ten organ pieces, designated pro organico or pro organicis, are found in Musae Sioniae (fantasias on Lutheran chorales) and Hymnodia Sionia (Latin hymns). The three monumental fantasias on Lutheran chorales anticipate the distinctive style Northern composers would later give to this musical form. These works, of impressive proportions, with their frequent intensely poetical passages, show the passionate temperament of a highly innovative composer. When setting each stanza, Praetorius uses current forms of counterpoint - imitation, diminution, and augmentation - but in such a way as to bring out the feeling of the words, immersing the worshippers in a pleasantly evocative musical atmosphere, while the chorale melody is heard in each voice. To keep the listener's attention, he employs constantly varied timbre and instrumental colour. As he himself writes in the introduction to the first volume of Musae Sioniae, "If desired, this variety of instrumental colour can be obtained on the organ through a dialogue between two or three manuals, and not only will scholars and professional musicians find this pleasing, but the members of the congregation also will find the sounds sweet and delicate." This constant concern for instrumental variety, and his love of refined, delicious timbre, give his music a seductive power similar to that of the Counter-Reformation. His criticism of Palestrina's polyphony is striking proof that for him, the musical setting must before all else illustrate the meaning of the text:: he writes in the third part of his Syntagma Musicum, "Although these compositions [of Palestrina] obey all the rules of counterpoint, they do not meet the requirements of truly fine music. As a result, the worshipper cannot understand the service - which is the precise purpose of the music -for the fugues take his attention away from the emotions expressed by the words." The fantasia on Ein feste Burg is a setting of Luther's chorale, the musical manifesto of the Reformation: "A. mighty fortress is our God, a trusty shield and sword. He will deliver us from all the evils that surround us. The ancient, wicked fiend is roused up again us. His great power and deep cunning are his fearful weapons. He has no equal on earth? Praetorius's setting does not fail to render the forceful images in the text. For example, the strophe describing the Devil's power and cunning resembles a real battle in which vigorous passages of semi-quavers depict his endless attacks. All this sound and fury is repeatedly punctuated by the long notes of the cantus, which declaims final victory over the forces of evil. Praetorius composed the chorale Wirglauben all' an einen Gott on an essential text, the Credo of Luther's catechism: "We all believe in one God, Creator of Heaven and Earth, who has become our Father that we may be His children. He wants to provide for our needs, protect our souls and bodies and preserve us from all snares. No evil can hurt us; He cares for us and watches over us. All things are in His power". The first stanza of the chorale is illustrated by calm, regular polyphony, with the melody appearing soon in the bass line, symbolizing unshakeable faith. Then passionate virtuoso passages break in, ensuring great vitality to the musical discourse. The melodic and rhythmic structure of the following stanzas continues to underline the meaning of the text. Of particular interest are the calm gentle minims used to depict the Father's tenderness. In the last verses, only the bass line is ornamented, and the melody appears in the treble in an impressive version of the vertically harmonized chorale, which irresistibly draws the listener into this powerful musical statement of Christian faith. The third fantasia, Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam, is 411 bars long and is doubtless the longest organ piece composed in this period, but it holds the listener's attention by the use of highly varied rhythms (in particular, effective switches between binary and ternary time-signatures). The text is as follows: "Christ our Lord came to Jordan, according to His Father's will. He was baptized by St John to fulfil His work and mission. There He instituted Baptism to wash away our sins and quench the bitterness of death by His own blood and wounds, and from this we are born again". Needless to say, Praetorius uses the same type of musical symbolism here as in the previous pieces. The calm swell of the river Jordan, in the third verse, is particularly noteworthy. This noble harmony in minims is punctuated discreetly by the chorale melody, which should surely be brought out by the performer. The result is a remarkably calm and intensely poetic grandeur. Calling these pieces "fantasias", and using the music to underline the words of Lutheran chorales places Michael Praetorius well ahead of his time, for this style was to become more and more frequent, reaching its crowning point with the Northern organists in the second half of the 17th century and, finally, with Johann Sebastian Bach._ This musical technique faithfully follows Luther's principles: the Word and the text set to music are equally important, and an organist is thereby raised to the rank of a preacher. The verses of the six Latin hymns set for the organ are used for Vespers in the Lutheran liturgy, performed alternatim. In each one, the entire melody appears in long values as a cantus firmus. Above each of these slow bass melodies floats elaborate counterpoint containing many imitations of the cantus. The broad palette of organ tone colour is magnificently exploited in these pieces, and Praetorius's advice to use different registrations on two or three manuals is fully justified. For example, although no precise instructions are given, an echo treatment in the Chrimas hymn Summo Parenti gloria and in O Lux beata Trinitas seems absolutely necessary. In the variations on Nun lob' mein Seel' den Herren, the embellished chorale tune is found in the treble. The structure is reminiscent of a madrigal rather than a motet, which is not the case with his setting of plainsong hymns. The three lower voices are written in the polyphonic style of contemporary airs or dances, and imitate the motifs of ornamentation and diminution used in the treble line. These two variations seem to indicate a dialogue of two choruses, although once again this is left to the discernment of the performer. Lastly, this piece should certainly be played manualiter, as neither the melody nor the rhythm of the bass voice is suited to a coherent pedal treatment. Altogether, performing Praetorius's organ pieces requires considerable flexibility. In the first edition, the polyphony is written out in four or five separate parts, though he himself specifies that organists may copy them out in German tablature. The most important question is whether or not the Pedal should be used. Praetorius himself gives no clue. The impossibility of playing the polyphony c>n manuals alone in some passages, whereas in others the bass line is in a virtuoso style quite unsuited to the Pedal, must guide the player. There are, however, various solutions: for example, another line can be played on the Pedal. In Vol.3 of Syntagma Musicum, Praetorius deals with ornamentation in organ music._ He describes the sinfonia as a sort of instrumental prelude or interlude and adds that if no players of other instruments are available, the organist can play a sinfonia alone, adding pleasant embellishments ("lieblichen Mordanten"). He also provides a list of the various ornaments used, with the performance of them written out: the tremulo, which organists call "mordant", and can be either long or rather short (tremoletto), the gruppo used at cadence-points, the tiratae which are rapid passages linking the notes of an interval. He specifies that the gruppo and tiratae are to be played fast and very distinctly, whereas the tremulo requires more of a slurred effect. This style of ornamentation in polyphony resembles the examples found in the English virginal school. The last important question to be answered by performers is: what instrument is appropriate for Praetorius's works? In De Organographia, the second volume of Syntagma Musicum, he gives an extensive list of both recent and older organs in Germany, along with their specifications. The tonal richness of these instruments is stunning. At that time, the entire art of organ building had already been brought to completion, with a vast variety of stops such as Gemshorn, Viola da Gamba, Rankett, Doppelflote (double mouthed Flute), and all kinds of metal or wooden flutes and reeds. Pedal stops often covered the whole range from 32 feet to 1 foot. The renowned organ-builder Esaias Compenius (1560-1617), a friend of Praetorius's, helped him in writing this important theoretical work on the organ, and the instrument he built in 1615 at Buckeburg is a perfect illustration of the spirit of the age. It had 48 stops, three manuals and Pedal. There were nine wedge-shaped bellows, and the double keys d sharp/e flat and g sharp/a flat enabled mean-tone temperament to be used in an unusually large number of keys. The only surviving complete instrument built by Esaias Compenius is in Frederiksborg Castle: it was built in 1605 for Hesse Castle near Wolfenbuttel and then offered to the King of Denmark, being installed in Frederiksborg in 1617. Praetorius, giving the specification of this organ, stresses that although all the pipes are made of wood, it is nonetheless a magnificent instrument. There is no doubt that this type of instrument sounds better in a chapel than in a church, but then Praetorius makes no secret of his love of delicate tone colours. And when rendering his organ pieces, it is essential to use just such an instrument, with a wide palette of refined and noble tone colours. It is equally important to use the mean-tone tuning described in Syntagma Musicum. The Scherer organ used in this recording is one of the very few remaining examples of early 17th century German organ building. Enjoying as it does the clear and generous acoustics of the church, it gives a moving and convincing rendering of these works, and its rich yet refined tone colours express the poetic power of the music perfectly, bringing to life again the enigmatic counterpoint of Michael Praetorius, the father of Protestant organ music.

This post has been edited by kgkk on 02-09-2011, 21:36 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Powered by Invision Power Board v1.3.1 Final.