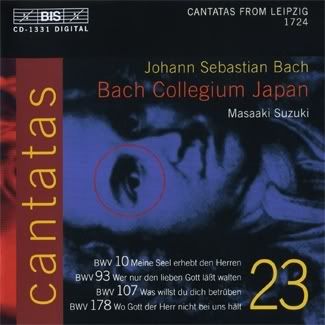

Johann Sebastian Bach - Matthaus- und Johannespassion[Suzuki, BIS, 5 CDs][EAC/FLAC+CUE/COVERS/BOOKLETS]

Johann Sebastian Bach - Matthaus- und Johannespassion[Suzuki, BIS, 5 CDs][EAC/FLAC+CUE/COVERS/BOOKLETS]One could trace the roots of Bach’s passions all the way back to Greece, especially in relation to the role of the chorus as both actor and commentator. But the specific liturgical antecedents date from the medieval plainsong passions, in which three priests intoned the crucifixion accounts on the days of Holy Week in music that made no claim to "drama" as that term is customarily applied to later music. This liturgical monophony carried each of the four accounts which were assigned to specific days of the week before Easter. The first German passion settings were by Johann Walther in 1530, using Luther’s translations of Matthew and John. By the late 16th century the typical German plainsong passions augmented the Gospel texts with devotional choruses at the beginning and end, usually of a simple syllabic type and with few if any repetitions of text. In the late Renaissance, a new choral type emerged, the so-called motet passion, in which there was no solo singing at all, although the choral texture was sometimes varied in an attempt to represent the character being portrayed. Later a composite evolved in which accounts from all four Gospels were incorporated: The Seven Last Words of Christ from the Cross. The motet style offered composers opportunities for increased expression, but it limited dramatic realism in not making use of soloists in the character portrayals.

In the early Baroque, several different traditions came into contention as composers began to expand the parameters. Recitative replaced plainsong, instrumental accompaniment was introduced, choral writing was freed from earlier constraints. Germany became a center for these innovations, and by the middle of the 17th century non-biblical texts began to be included, drawn from the enormous Lutheran chorale repertoire, but also and significantly from freshly composed poetry intended for arias and choruses. A new musical form was created, the

oratorio passion, which shortly evolved in north Germany into the Hamburg opera passion. Notable among its innovators was Barthold Heinrich Brockes, whose passion text, largely a paraphrase of scripture, was set by Handel, Telemann, Keiser, and others. The Hamburg style of biblical paraphrase was widely copied during Bach’s years. Bach’s obituary, written by his son C. P. E. Bach with the help of his father’s pupil Agricola, mentions five passion settings by the elder Bach. Some doubt exists as to the accuracy of that statement. The John and Matthew accounts are the only ones that survive complete. A setting of Mark has been partially recreated. As to others, most scholars believe it unlikely that complete passion settings of the scale of John and Matthew would have disappeared without a trace.

Disc I - IIIMatthaus-Passion, BWV 244

Disc I - IIIMatthaus-Passion, BWV 244Passion unseres Herrn Jesu Christi nach dem Evangelisten Matthäus

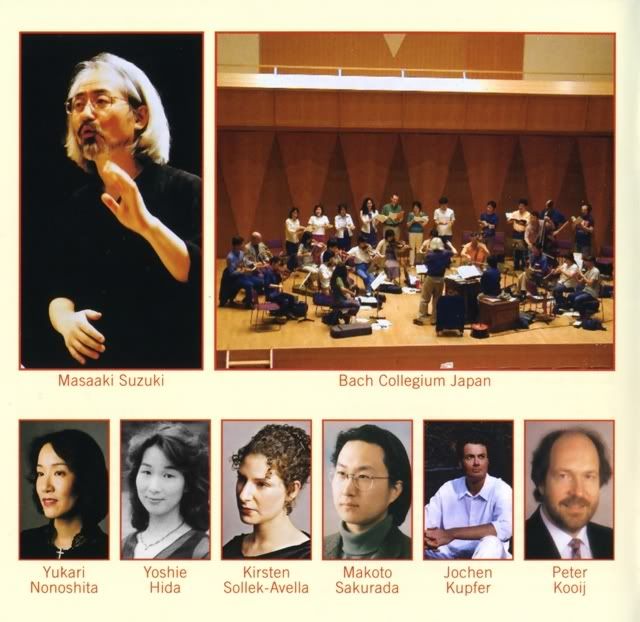

St. Matthew Passion - La Passion selon Saint MatthieuNancy Argenta, soprano

Robin Blaze, counter-tenor

Gerd Türk, tenor (Evangelist)

Makoto Sakurada, tenor arias, Testis II

Peter Kooij, bass (Jesus)

Chiyuki Urano, bass arias, Judas, Petrus, Pilatus, Pontifex

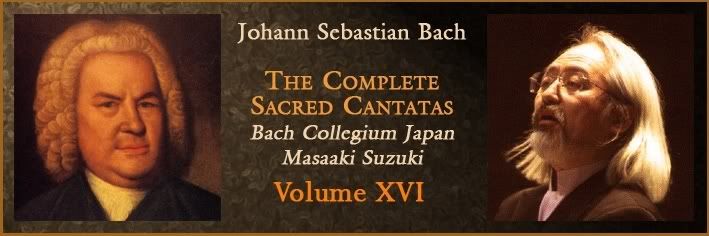

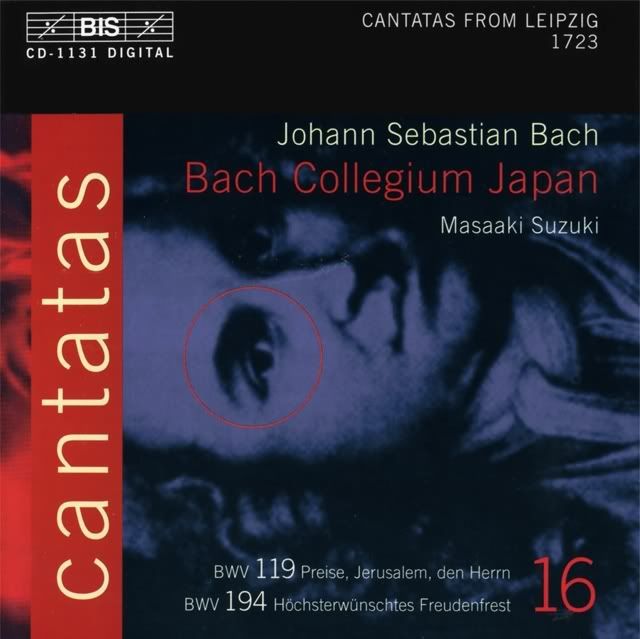

Bach Collegium Japan

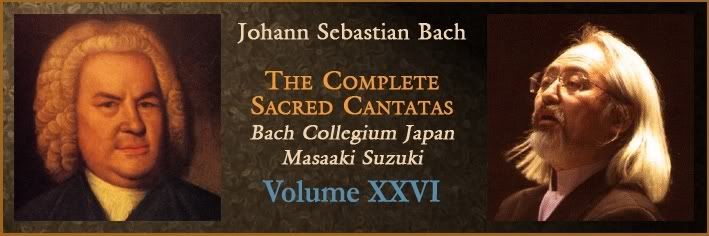

Masaaki SuzukiTracklistDisc I -

Part I [69:35]

Disc II -

Part II, beginning [53:50]

Disc III -

Part II, ending [42.12]

Recorded March 1999 at the Kobe Shoin Women’s University Chapel, Japan

Sound engineer: Marion Schwebel. Recording producer: Hans Kipfer

© 1999 Grammofon AB BIS CD 1000-02After a wonderfully vital reading of the

St. John Passion comes the greatest challenge of all. It may come as a surprise that the ultimate interpretative exploration has been taken up so early in the complete cycle of sacred music planned by BIS. Few, though, would doubt Suzuki’s instincts for the right thing: he is an extraordinarily informed Bachian who has established himself as gauging the spiritual essence of music too often sacrificed for surface vanity. This often gives Suzuki a distinctive quality, as this new recording demonstrates in its floating spaciousness, beautifully weighted textures and a reverence, even worderment. It is plain in the incandescent opening chorus, as glowingly beautiful as you will hear, and also in the arched pathos of ‘O Mensch bewein’; there is a rooted sincerity to the narrative which seeks only to serve, not to impose or impress. Much of this comes down to Gerd Türk’s intensely alert Evangelist. He makes discreet poetry out of his role (...) and this suits Suzuki’s evolving and patient, almost purposely undistracted pacing of events. Suzuki lets the tide pull him into the post-Crucifixion drama and meditation, rather than directing the tension-filled last hour of what is, unarguably, one of the most tantalisingly emotional experiences in music. Some may find also that he is too reticent to fling himself into a type of oratorian theatricality, though, on its own, that is not the true source of my discomfort. For all the attractions of Suzuki’s journey of contemplation, the

St Matthe is a rather different prospect from most of the cantata œuvre. Plainly, I miss the stark physicality of the passion drama, the palpable human pain, the singers as protagonists prepared to take risks in a believable way. This recording followed a period of intense preparation as well as performances around Easter 1999. With every articulation duly noted and rehearsed, there comes a moment when repeated patterns of phrasing appear as quasi-mannerisms, often involving a wafting legato, and thus limiting characterisation and blocking spontaneity. This does not detract, however, from the voloptuous dialogue of Robin Blaze and the flutes in ‘Buß und Reu’ (‘Können Tränen’ is also very special), the impeccably delivered, if slightly shrill-sounding Nancy Argenta, and generally the lovingly formed set-pieces in which Peter Kooij’s Christus is a notable achievement. There are indeed many impressive and affecting moments in this

St Matthew; the sheer beauty of Suzuki’s conception may be enough for many listeners – as well as the outstandingly fine and consistent playing and singing – as has been the case in the majority of his cantata releases. For me, however, there isn’t enough truly penetrating artistry where the music-making resonates beyond its own set terms. It’s an elusive mix, which is rarely discovered these days, and one perhaps which requires a broader vision of the

St Matthew Passion’s cultural significance than Suzuki can give it.

Jonathan Freeman-Attwood, Gramophone, March 2000[/color]

Disc IV - VJohannespassion, BWV 245

Disc IV - VJohannespassion, BWV 245Passion unseres Herrn Jesu Christi nach dem Evangelisten Johannes

St. John Passion - La Passion selon Saint JeanFassung / Version IV, 1749 Ingrid Schmithüsen, soprano

Yoshikazu Mera, counter-tenor

Gerd Türk, tenor (Evangelist; tenor arias in Appendices)

Makoto Sakurada, tenor arias, Diener

Chiyuki Urano, bass (Jesus)

Peter Kooij, bass arias, Petrus, Pilatus

TracklistDisc IV, tracks 1-14 -

Part I [34:14]

Disc IV, tracks 15-24 & Disc II, tracks 1-16 -

Part II [76:50]

Disc V, tracks 17-19 - Appendices from Version II, 1725 [15:07]

Recorded April 1998 at the Kobe Shoin Women’s University Chapel, Japan

Sound engineer: Ingo Petry. Recording producer: Jens Braun

© 1999 Grammofon AB BIS CD 921-22 Bach seems to have performed his

St. John Passion on four Good Fridays during his tenure as Thomaskantor at Leipzig. Unlike his grander scale

St. Matthew Passion, however, he continued to make significant revisions to the

St John right up the last performance under his direction, on April 4th, 1749. Of the four versions, the second, dating from 1725, contains the most distinctive revisions, the first version (1724) and the last bearing close affinity with one another. Masaaki Suzuki and his talented Bach Collegium Japan have chosen Bach’s latest version as their source for the present recording. (...) What is refreshing about their approach is the importance afforded to the relationship between text and music, to the theological source of Bach’s inspiration, and the emotional impact of the story and the music on its audience. The role of the Evangelist, crucial to the lyrical unfolding of the story, and traditionally a tenor role, is sung with clarity and lightness of inflexion by Gerd Türk. His performance is eloquently measured, his phrasing well shaped and his articulation engagingly varied. All of which makes of him a riveting story-teller. The role of Jesus is taken by Chiyuki Urano, an artist with a warm-toned and resonant voice. From among the remaining soloists, Ingrid Schmidthüsen and Yoshikazu Mera make strongly appealing contributions in their respective arias and Peter Kooij (as Pontius Pilate and Peter) is, as ever, satisfying and affecting. Excellent, too, are the contributions of the Collegium’s choir of women’s and men’s voices. There is great textural clarity here, well balanced, furthermore, with the comparably lucid instrumental textures. Choral and instrumental articulation is incisive, propelling the rhythms with energy and urgency; the ‘Lasset uns den nicht zerteilen’ from Part II of the Passion is a lively example of the disciplined expression of which these artists are capable. Too disciplined for some, perhaps, but I certainly found my own emotions responding to it.

What more can I say, other than I found myself drawn into the drama from the start, at the same time finding much that struck me as fresh in matters of interpretation, and tonally of great beauty. Mera’s ‘Es ist vollbracht!’ is superbly sung, with an effectively judged contrast between its

molto adagio and

vivace sections. Following on from that, there is a complementary serenity in Kooij’s ‘Mein teurer Heiland’, and a chilling sense of theatre in Türk’s

arioso, ‘Mein Herz in dem die ganze Welt’. It is in passages such as these that the excellence of the Collegium’s instrumentalists is underlined. I should have liked a shade more limpidity in the articulation of the aria ‘Zefließe, mein Herze’, but Schmidthüsen’s singing of it is admirable. In short, I have found myself entranced by the performance. (...) I have a feeling, albeit on slender acquaintance, that the present version will satisfy me more than any of its rivals. It seems to me a subtly poised balance between scholarship and communicative interpretation. And, very sensibly, the second disc contains, in addition, the three arias from the 1725 version that cannot be found elsewhere. For me, at least, this is a major recording event, and an eminently satisfying one.

Nicholas Anderson, Gramophone, April 1999 Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian BachThree languages-, 68- and 44- pages-booklets in .pdf format included,

with extensive notes on works, performers and Cantatas’ text in German and English.[/size][/font]